What is rotavirus?

Rotavirus is a virus that infects the stomach and intestines, resulting in what we call gastroenteritis (gastro- = stomach, entero- = intestines, -itis= infection/inflammation of) Symptoms include vomiting followed by fever and watery, non-bloody diarrhea. One third of children will have high fever due to rotavirus infection. The amount of fluid loss from vomiting and/or diarrhea can be significant, especially for infants and young children who have less fluid to spare in their small bodies. Inability to rehydrate due to vomiting compounds the fluid loss patients experience and can result in rapid onset of dehydration for patients of any age, but especially the youngest. Symptoms typically last 3-7 days.

How is rotavirus spread?

Rotavirus is spread by the fecal-oral route. The virus is shed in the stool and contaminates hands that are not adequately washed with soap and water after defecation or after changing dirty diapers of an infected child (hand sanitizer does not kill/disinfect rotavirus). Contaminated hands then introduce the virus to a new individual during snacks/meals, or by other direct or indirect contact with the mouth. The virus can remain viable on contaminated surfaces such as doorknobs, cabinet/drawer handles, furniture and toys for weeks to months. Not surprisingly, young children who are curious, exploratory, mobile, and mouthy (i.e. constantly putting their hands and other objects in their mouths or putting their mouths directly on objects) are among those at highest risk of getting infected when exposed. The stool of an infected person is loaded with contagious material – estimated between 1 million and 1 billion times more than is necessary to infect another person. After becoming infected, a patient sheds the virus in their stool for approximately 10 days.

How long after exposure will someone develop symptoms?

The incubation period is quick – typically less than 48 hours.

What are the complications of rotavirus infections?

As noted above dehydration is the biggest concern and is the most common reason for hospitalization due to rotavirus infections. When an individual vomits or has diarrhea, in addition to fluids they also lose electrolytes such as sodium, chloride and potassium. Electrolyte imbalances can affect the brain, blood pressure, muscle function and electrical activity in the heart. Low sodium levels can cause seizures, which occur in 2-3% of children with rotavirus infections. Abnormal potassium levels can cause dangerous heart rhythms. Intussusception – a blockage caused by an inflamed portion of the intestine telescoping in on a neighboring portion – is rare but occurs in approximately 1 in 100,000 infections. Death is even more rare but has occurred due to severe dehydration, brain inflammation and/or abnormal heart rhythms secondary to rotavirus infections.

A less serious and temporary, but impactful complication due to the dairy-rich diet of U.S. culture is lactose intolerance. Lactase, the enzyme that breaks down lactose, lives along the lining of the intestines and can be temporarily wiped out while the intestinal lining is inflamed and trying to heal. Consumption of dairy products prior to healing and restoration of lactase results in bloating, gassiness, belly distension, pain and potentially more diarrhea.

Is there a treatment for rotavirus infections?

No, unfortunately there is no specific treatment for fighting the virus. The focus of managing rotavirus infections is keeping the patient as hydrated as possible while also replenishing electrolytes. If a patient is unable to keep any food or liquids down due to vomiting they will need IV fluids to keep their blood pressure regulated and electrolytes in a normal range. We often recommend patients avoid dairy when possible due to the temporary lactose intolerance noted above. So far, pre- or probiotics have not been shown in published medical studies to reduce the duration or severity of illness in viral gastroenteritis such as rotavirus infections.

Read more about how we recommend hydrating children with vomiting or diarrhea.

How many people were affected by rotavirus infections prior to the vaccine?

Per the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Vaccine Education Center, prior to introduction of the rotavirus vaccine, “Each year in the U.S.:

- 2.7 million children, usually between 6 months and 24 months of age, became ill

- 500,000 children went to the doctor because of rotavirus illness

- 55,000 to 70,000 children were hospitalized

- 20 to 60 children died”

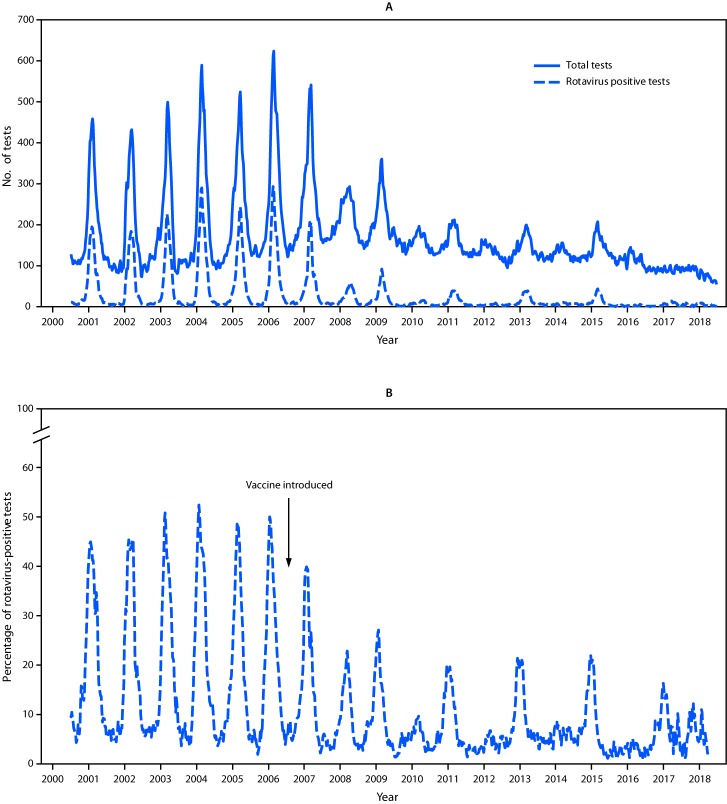

How has the vaccine affected the number of rotavirus infections in the U.S.?

The chart below from the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report published by the CDC in 2019 shows a significant decline in positive stool samples for rotavirus after introduction of the vaccine in 2006.

How long have rotavirus vaccines been available?

The vaccines used today became available in 2006 (Rotateq) and 2008 (Rotarix). Their predecessor is an example of how the U.S. vaccine safety monitoring system works to keep children safe.

The first rotavirus vaccine, called Rotashield, was approved in 1998 but is no longer available in the U.S. because it was found to cause intussusception at a rate between 1 in 10,000 and 1 in 30,0000 children – a much higher rate than the illness itself is known to cause. Because of reports of these blockages to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), this side effect was identified and further studied. Analysis of this data led to the removal of Rotashield and the development of our current, much safer vaccines. Doctors, parents, or anyone can make a report to VAERS which are reviewed by public health investigators and used to monitor and identify any concerning trends (i.e. safety signals) even after they have been extensively studied in pre-clinical and clinical trials. Because of the safety signals with Rotashield, clinical trials for Rotateq and Rotarix had a much greater number of participants to ensure similar safety signals could be better detected, if present, prior to licensure.

What type of vaccine is the rotavirus vaccine?

Rotavirus vaccines are live, attenuated vaccines, meaning they contain a weakened form of the virus that is enough for the body to build immune memory to protect against natural infection without causing actual infection by the virus. There are two different rotavirus vaccines available in the U.S.: Rotarix (given in 2 doses) and RotaTeq (given in 3 doses). Both are given as a liquid your child swallows, not by shot.

Note: if a parent or other close contact has a weakened immune system due to medical conditions or because of medical treatment, their medical professional may advise against the child getting a live vaccine such as rotavirus. Please inform the vaccine-ordering healthcare provider prior to administration if you think this may be applicable to your family’s health status.

When is the rotavirus vaccine administered?

Rotavirus vaccines are recommended for children starting at 2 months of age; 2nd and 3rd doses are typically administered at 4 and 6 months of age, respectively. The first dose should be given between 6 weeks and 14 weeks old, and the series should be finished by 8 months old. This schedule is based on studies showing the vaccine is safest and most effective when given early. Children 6 months to 2 years old are at highest risk for infection and complications. Rotavirus spreads easily among infants and young children. By administering the vaccine early in infancy, before this highest risk age range, we provide them with the best protection against severe illness, hospitalization, and potential complications from rotavirus.

What are the possible side effects of the rotavirus vaccine?

Most children have no serious side effects from the rotavirus vaccine. Common mild side effects include short-lived fussiness, mild fever, vomiting, or diarrhea. In clinical trials these mild side effects did not occur any more frequently than in the placebo group. Even in the newer and currently used rotavirus vaccines, intussusception remains a possible but rare side effect. Intussusception may result from 1 in 100,000 doses of our current rotavirus vaccines, but that rate is similar to how often children develop intussusception from rotavirus infection itself.

Why should I vaccinate my child against rotavirus?

Even though rotavirus is less common today, vaccination is still important. Rotavirus can spread easily. Because of the virus’s stability on commonly touched surfaces, good hand hygiene alone does not prevent all cases. If vaccination rates drop, rotavirus could become common again and we could once again see millions of children infected, tens of thousands hospitalized, and dozens of unnecessary childhood deaths every year. The vaccine protects not only your child but also helps prevent outbreaks in the community. Children who are “low risk” can still get severe rotavirus infections, and there is no way to predict which children will have serious illness or complications like dehydration, seizures or heart arrhythmias. Yes, there is a 1 in 100,000 risk of intussusception from the vaccine, but a similar risk exists if your child were to get infected with rotavirus. What is more, the high hospitalization numbers in young children lead to significant financial burden and time missed from work for parents and other caregivers.

On January 5, 2026 leadership of the Centers of Disease Control changed their list of universally recommended vaccines to align more with recommendations of “peer nations” like Denmark. Under this new schedule the CDC only recommends rotavirus vaccinations with “shared clinical decision-making,” not universally. So why should I vaccinate my baby if it’s not universally recommended by the CDC?

There are challenges with using Denmark as the benchmark for vaccine policy, and in this case for guidance on the necessity of rotavirus vaccination:

- Denmark has a population of about 6 million people. For context, in 2025-26, this is the approximate population of Maryland, approximately 2/3 the population of Virginia, 3/4 the population of New York City, and about 1.7% of the size of the U.S. population. Additionally, Denmark’s population is more homogenous and less ethnically diverse with different general health risk factors. Every year about 1,200 Danish children are hospitalized due to rotavirus infection (0.02% of the total population). Prior to universal rotavirus vaccination recommendations in the U.S. there were upwards of 70,000 annual childhood hospitalizations, which is coincidentally 0.02% of the total U.S. population (~300 million) at that time. So, a low percentage of a low number is low number (Denmark), but a low percentage of a high number is still a really high number, and 60,000+ more children would be estimated to require hospitalization compared to Denmark each year without this universal protection.

- Denmark has a universal, tax-funded healthcare system with heavy emphasis on free access. With better access to healthcare there are fewer premature, low-birthweight babies, and other health variables that put children at risk for complications due to rotavirus infections. Free access also creates fewer barriers for parents to bring their child in to be evaluated sooner, rather than later, when illness may have progressed to the point of needing IV fluids and hospitalization. This point is not brought up to debate the free-market U.S. system vs the universal Danish system. Rather, to point out that basing U.S. healthcare decisions on a country with a significantly smaller and less-diverse population and a completely different healthcare system is not the most helpful approach.

Knowing that the size and overall health of the Danish population, and their healthcare system itself are vastly different from those in the United States, it does not make sense to translate their approach to population medicine and infectious disease control in the U.S. The physicians of Pediatric Associates of Richmond therefore continue to recommend rotavirus vaccination to all infants (unless they have a medical condition that precludes administration). Many of our doctors have been working long enough to have seen and cared for the scores of hospitalized children with rotavirus-associated dehydration and other complications prior to 2006. Our approach keeps large numbers of children home, healthy, and out of the hospital, and allows parents to continue working to provide for their families without having to worry about time missed from work or preventable medical bills.

Resources

2024. “Rotavirus Infections”, Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics, David W. Kimberlin, MD, FAAP, Ritu Banerjee, MD, PhD, FAAP, Elizabeth D. Barnett, MD, FAAP, Ruth Lynfield, MD, FAAP, Mark H. Sawyer, MD, FAAP

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/rotavirus-infection-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis

https://www.chop.edu/vaccine-education-center/vaccine-details/rotavirus-vaccine

Prevention of Rotavirus Gastroenteritis Among Infants and Children. Margaret M. Cortese MD, Umesh D. Parashar MBBS MPH. Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (2009).

Flynn TG, Olortegui MP, Kosek MN. Viral gastroenteritis. Lancet. 2024 Mar 2;403(10429):862-876. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)02037-8. Epub 2024 Feb 7. PMID: 38340741.

Hallowell BD, Parashar UD, Curns A, DeGroote NP, Tate JE. Trends in the Laboratory Detection of Rotavirus Before and After Implementation of Routine Rotavirus Vaccination – United States, 2000-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Jun 21;68(24):539-543. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6824a2. PMID: 31220058; PMCID: PMC6586368.

Rotateq package insert: https://www.fda.gov/media/75718/download