What is mumps?

Mumps is a viral syndrome most well-known for the chipmunk-looking cheek swelling it causes. Initial symptoms typically include a few days of fever, fatigue, malaise, muscle aches, loss of appetite, and headache. These symptoms are followed by inflammation of saliva-producing glands. The most common salivary gland affected is the parotid gland, which is located near the angle of our lower jawbones, below our ears. Parotid gland inflammation results in significantly swollen and painful cheeks; such inflammation can last up to 10 days.

Those seem like undesirable, but relatively minor symptoms. Why do we vaccinate against mumps?

In addition to the above symptoms, mumps can also affect reproductive organs, the nervous system, and the pancreas. Infection of one or both testicles (aka, orchitis) is the most common complication of mumps infection. Orchitis typically develops 5-10 days after cheek swelling, causes swollen and severely painful testicles, and can result in decreased fertility or complete sterility if both testicles are affected. Orchitis occurs in approximately 30% of males with mumps. Between 30 and 50% of unvaccinated men who have mumps orchitis will develop testicular atrophy (aka permanent decrease in size) after the primary inflammation has resolved; this occurs in less than 1% of vaccinated males. Less commonly (in about 5% of post-pubertal females) mumps can cause infection of the ovaries resulting in severe lower abdominal pain, fever and vomiting. The risk of female infertility from ovarian mumps infection is unclear. Mumps has been documented to cause miscarriages when infection occurs in the first trimester. Mumps can also cause mastitis (breast infection), and does so in 30% of unvaccinated women.

Prior to vaccine availability, mumps was the leading cause of viral meningitis in children. Meningitis is infection of the lining that surrounds our brain and spinal cord, and occurs in up to 10% of patients with mumps. Almost all children survive mumps meningitis, but many are left deaf. Mumps infections were so prevalent before the vaccine was introduced in the late 1960s that it was the most common cause of deafness that can develop after children are born. This changed dramatically after vaccine administration became the standard of care. Less commonly (about 1 in 6,000 patients in the pre-vaccination era), mumps infects the brain itself (aka encephalitis).

Pancreatitis occurs in 4% of unvaccinated patients but <1% of vaccinated patients. The pancreas has many functions, but most notably makes insulin and digestive enzymes.

How is mumps spread?

Mumps is spread through contact with respiratory droplets (e.g. saliva and nasal mucous). Those droplets can be aerosolized by coughing or sneezing, directly transmitted through kissing or sharing of cups/straws/eating utensils, or indirectly transferred on commonly touched surfaces in homes, schools, stores, etc. Rapid spread of mumps is most common when individuals are in close quarters for extended periods of time, such as a classroom or dormitory. There is typically a 2.5-week period between when a person is exposed and when they start to show symptoms. Patients are most contagious just before salivary gland swelling and for the 5 days that follow.

Is there a treatment for mumps?

There is no specific anti-viral medicine for mumps. Unfortunately, we can only provide “supportive care” to help minimize the symptoms while the immune system fights off the virus. Supportive measures include cold packs for swollen and painful salivary glands and testicles, supportive underwear to minimize movement of the inflamed genitals, and over-the-counter pain relievers. Because there is no anti-mumps medicine, and complications can result in infertility, nervous system infection and/or deafness, and inflammation of the pancreas, the best treatment is mumps prevention through vaccination. Vaccination also reduces time missed from school/daycare/work, and helps limit the frequency and severity of outbreaks.

What is the history of the mumps vaccine?

The first mumps vaccine was licensed in 1967. The lead researcher was Dr. Maurice Hilleman, who isolated the virus from his infected 5-year-old daughter. In 1971, a combined measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) vaccine was licensed after head-to-head studies showed that the combination vaccine had similar effectiveness and safety compared to receiving each of the 3 components through separate injections. Individual mumps vaccines have not been available in the United States in the decades since.

What kind of vaccine is MMR?

The mumps vaccine is a live, attenuated vaccine. This means that the vaccine contains live mumps virus, but virus that has been significantly weakened to the point that it cannot cause actual disease in an individual with a normally functioning immune system. Though weakened so it cannot cause actual disease, this type of vaccine still creates a robust immune system response by our bodies. A video further explaining this process can be found here.

Note: individuals with weakened immune systems due to medical condition or medical treatment should not receive live vaccines unless otherwise specified by their healthcare professional

How effective is the MMR vaccine to prevent mumps?

One dose provides 72% protection against mumps. Two doses provide 86% protection. While this is not quite as good as the 97% protection against the measles and rubella viruses, it still provides a huge layer of protection for the individual and the community. Those in that 14% who still get mumps despite being fully vaccinated have shorter, milder courses of illness and much less risk of the complications mentioned above compared to unvaccinated individuals. Per CDC estimates, frequency of orchitis drops from 30% to 6% when individuals are fully vaccinated. All other complications noted above drop below 1% of infected individuals with vaccination.

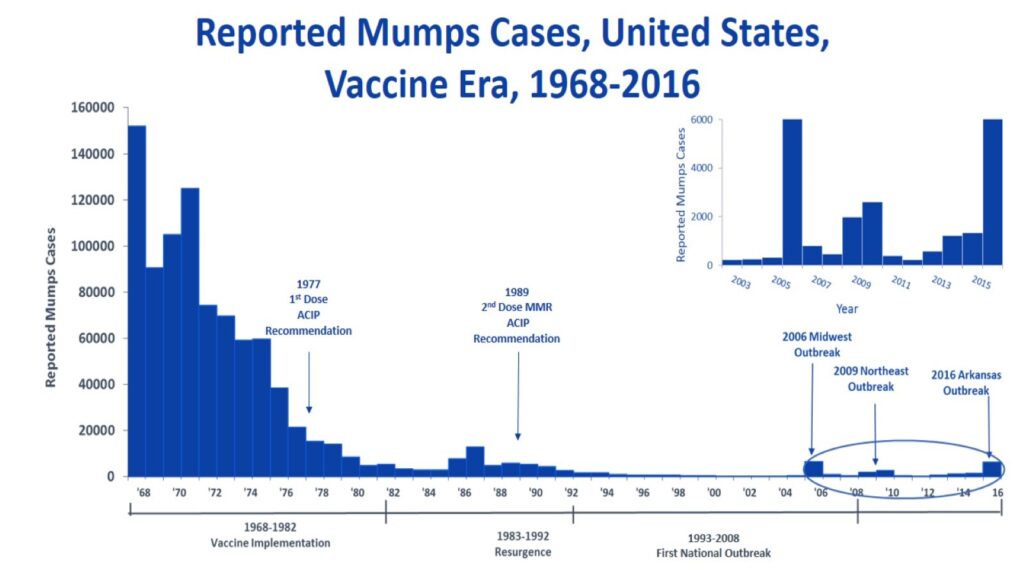

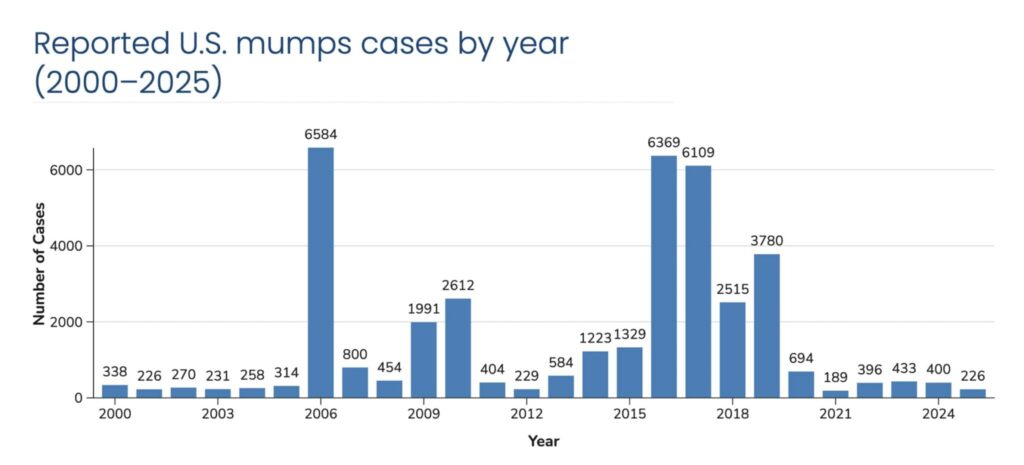

Cases reported to the CDC in 1968 (prior to availability of the mumps vaccine) totaled just over 152,000. Administration of a single dose of MMR vaccine became standard of care in 1977. By 1985 there were only 2,500 reported cases annually in the United States. In 1989 a measles outbreaks in school-aged children led to the recommendation of a second dose of MMR vaccine. By the turn of the century, the United States was averaging between 200 and 500 reported cases annually. Years with outbreaks (2006, 2016-2019) saw case numbers between 2,500 and 6,500 annually, and act as a reminder of how suddenly mumps infections can escalate. As of September 11, 2025 there have been 226 reported cases this year.

When is the vaccine administered?

The vaccine is two doses. The first dose is typically administered between 12-15 months of age. The second dose is typically given between 4-6 years of age and prior to the start of kindergarten. Maternal antibodies that cross through the placenta and are transferred through breastmilk protect a baby until about 6 months of age. There are special situations in which an infant between 6-12 months of age may receive an additional dose early. This is recommended during local outbreaks of 1 of the 3 infections, or for infants traveling to areas where measles, mumps or rubella are circulating. Infants who receive an MMR vaccine between 6-12 months still need the two-dose series because an infant’s immune system does not typically produce high enough, and long-lasting enough, antibody levels to protect them for the rest of their lives.

Is the vaccine safe? What are the possible side effects?

Yes! The vaccine is safe. Most individuals receiving an MMR vaccine will have no side effects.

The temporary (usually less than 24-48 hours) possible side effects include:

- Localized reactions (such as redness, soreness, swelling and the injection site), up to 40% of recipients

- Drowsiness in 27-45% of recipients

- Decreased appetite in 21-45% of recipients

- High fever 5-12 days after the vaccine is given, up to 35% of recipients

- Mild measles-like rash, less than 5% of recipients. Also typically 1-2 weeks later

- Temporary decrease in platelets (thrombocytopenia), 1-3 cases per 100,000 recipients

- Febrile seizure in 0.04% of children under age 4 receiving the combined MMR and Chicken Pox vaccine (PAR has not, and does not, administer this combination vaccine). While simple febrile seizures are extremely scary to experience, thankfully they do not cause short- or long-term complications for the brain, slow development, or decrease learning or IQ.

Why do people think the MMR vaccine causes autism, and how do we know that it doesn’t?

In 1998, a British medical journal called The Lancet published an article by Andrew Wakefield claiming that the MMR vaccine increased the risk for autism and colitis (inflamed large intestine). This was a case series in which 12 children were reviewed, and 8 children were diagnosed with autism after the vaccine. This was investigated and the article was eventually retracted in 2010 by The Lancet after investigators found that there were ethical violations (financial gain/conflict of interest) and deliberate fraud with selection/falsification of data. They also found that the children in the study were carefully selected, and Wakefield’s research was funded by lawyers hired by parents involved in lawsuits against vaccine manufacturers.

Since Wakefield’s case series and article, there have been 18 large studies in seven different countries in Europe, North America, and Asia. These studies involved hundreds of thousands of children who were grouped into two groups: those who received the MMR vaccine and those who did not. The two groups were matched for multiple variables (healthcare-seeking behavior/accessibility, socioeconomic background, and medical background). All 18 studies have shown that there was no difference or increased risk of autism associated with receiving the MMR vaccine.

Resources

2024. “Mumps”, Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics, David W. Kimberlin, MD, FAAP, Ritu Banerjee, MD, PhD, FAAP, Elizabeth D. Barnett, MD, FAAP, Ruth Lynfield, MD, FAAP, Mark H. Sawyer, MD, FAAP

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/mumps

https://www.chop.edu/vaccine-education-center/vaccine-details/measles-mumps-and-rubella-vaccines

https://historyofvaccines.org/diseases/mumps

https://www.cdc.gov/mumps/vaccines/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/surv-manual/php/table-of-contents/chapter-9-mumps.html

https://rx.ph.lacounty.gov/RxMumps0917rev0918

Eggertson L. Lancet retracts 12-year-old article linking autism to MMR vaccines. CMAJ. 2010 Mar 9;182(4):E199-200. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-3179. Epub 2010 Feb 8. PMID: 20142376; PMCID: PMC2831678.