What is Measles?

Measles is a highly contagious viral illness that starts out looking like other cold viruses but can later lead to a wide range of complications. Initial symptoms include high fever, fatigue, and the three C’s: cough, coryza (runny nose), and conjunctivitis (pink eye). After two to three days, patients may develop Koplik spots (raised bluish-white spots in the mouth). Three to five days after symptoms begin, a rash develops. The measles rash typically starts as red spots along the forehead hairline that progressively spread downward to the face, the neck, and then body. Imagine dumping thick red paint on the head, and watching it slowly drip down and covering the remainder of the body from head to toe.

What are the possible complications of measles?

Complications occur in approximately 30% of infected individuals. Measles infections temporarily weaken our immune systems and make us more susceptible to simultaneous bacterial infections of the ears, lungs, or blood stream. Measles can also destroy our memory T cells. Memory T cells are white blood cells made after fighting infection that remind our immune system how to fight that viral or bacterial infection in the future. When these T cells are destroyed, we experience immune amnesia – our bodies don’t remember how to fight off the infections we’ve previously fought and must learn all over again in a process that can take several years. One observational study found that while some infected children had as little as 11% destruction, others experienced elimination of up to 73% of these memory T cells due to recent measles infection.

The following are the approximate rates of other measles complications:

Ear infections: 1 in 10 infected children.

Diarrhea: 1 in 10 infected patients of all ages. Younger children with diarrhea are much more susceptible to developing subsequent dehydration.

Pneumonia (lung infection): up to 1 in 20 infected children. Pneumonia is the leading cause of death in young children infected with measles.

Encephalitis (brain swelling that cause seizures, hearing loss, intellectual disability or death): 1 in 1,000 infected children.

Hospitalization: 1 in 5 unimmunized patients in the U.S. requires hospitalization due to measles infection or its complications; children under 5 years old have the highest rates.

Death: 1 to 3 of every 1,000 children infected with measles will die due to complications.

Subacute Sclerosing Panencephalitis: rare, less than 1 in 10,000. Occurs 7-10 years after infection, is fatal, and results from progressive decline of the brain and nervous system.

How is measles spread?

Measles is one of the most contagious infections known to humankind. Approximately 90% of susceptible individuals will get infected after direct contact with – or exposure to airborne droplets from – an individual infected with measles. Individuals are considered immune, and not susceptible, after natural infection or completing the two dose measles vaccine series. Measles can be spread by person-to-person contact or by inhaling airborne droplets. Infectious droplets aerosolized by the cough or sneeze of an infected individual can remain airborne for up to two hours. This makes it very easy to spread in public spaces (examples: schools, stores, airports, public transportation, densely attended sporting or entertainment events, etc.). Symptoms may begin anywhere from 6 to 21 days following exposure, but the average incubation period is 13 days. Infected individuals are contagious from five days before the rash appears to four days afterward.

Can measles be treated?

There is no antiviral treatment for measles. The treatment for measles is supportive care such as fluids for dehydration, fever reducers for comfort, antibiotics for bacterial superinfections (such as pneumonia or ear infections), and specific treatments for other complications that may occur. Vitamin A supplementation also plays a role in supportive treatment as Vitamin A deficiency has been shown to prolong the illness and delay recovery. Measles can also cause Vitamin A levels to fall during illness. Vitamin A doses should be confirmed with a medical professional prior to administration. These doses are based on age, and too much Vitamin A can damage the liver.

How common were measles infections before introduction of the vaccine?

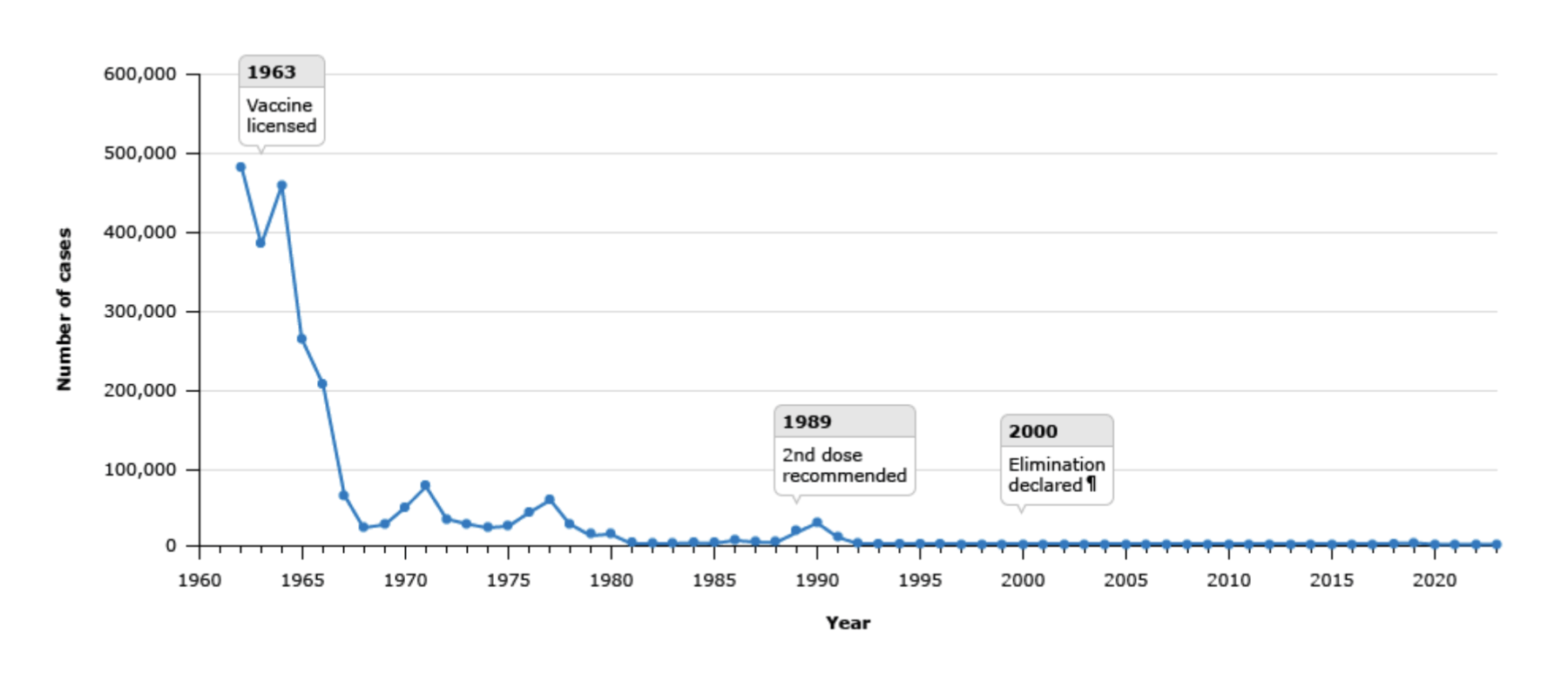

Prior to introduction of the first measles vaccine in 1963, annual rates of reported infections in the U.S. were between 400,000 and 500,000 (the CDC estimates the actual number was 3-4 million). Of those reported infections, each year approximately 48,000 were hospitalized, 1,000 developed brain swelling (encephalitis), and 400-500 died. A remarkably sharp decline in measles cases occurred after introduction of the vaccine (see CDC graphic below). Measles now primarily occurs in resource-limited areas, or areas of low vaccination rates. In 2023 there were only 59 reported cases of measles in the U.S. In 2024 the number increased to 285. As of September 30, 2025, there have been 1,544 cases (66% of which were pediatric patients) year-to-date. 86% of them have been due to outbreaks (outbreak = three or more related cases), 92% were unvaccinated or had unknown vaccine status, 4% had received one dose of vaccine, 4% had received both doses. Three individuals (two children) died from their measles infection between January 1 and September 30, 2025.

What type of vaccine is the measles vaccine?

The measles vaccine is a live, attenuated vaccine. This means that there is actual live virus, but one that has been significantly weakened to the point that it cannot cause actual disease in an individual with a normally functioning immune system. Though weakened so it cannot cause actual disease, this type of vaccine still creates a robust immune system response by our bodies. Attempts to create an inactivated vaccine (i.e. no live virus, like the polio shot) have not produced an adequate protective immune response. The initial live, attenuated vaccine against just measles was created in the 1960s but resulted in too many side effects. Vaccine researchers then fine-tuned the degree to which they weakened the virus to ensure an adequate immune system response while causing the fewest side effects possible. A video further explaining this process can be found here.

In 1971 the measles vaccine was combined with individual vaccines for mumps and rubella after head-to-head studies showed equal effectiveness and no more side effects with the combined vaccine compared to doing the three components separately. A separate, individual measles vaccine has not been available in the U.S. in decades. Note: individuals with a weakened immune system due to medical conditions or as a consequence of medical treatment should not receive live, attenuated vaccines unless otherwise specifically recommended by their healthcare professional.

How effective is the measles vaccine?

On an individual level, a single dose of MMR vaccine produces adequate protection against measles in 93% of individuals. Two doses of MMR vaccine produce adequate protection against measles in 97% of individuals – a number that meets and surpasses the goal of 95% community herd immunity, which is required to stop ongoing transmission of the virus.

When is the vaccine administered?

The vaccine is two doses. The first dose is typically administered between 12-15 months of age. The second dose is typically given between 4-6 years of age and prior to the start of kindergarten. Maternal antibodies that cross through the placenta and are transferred through breastmilk protect a baby until about 6 months of age. There are special situations in which an infant between 6-12 months of age may receive an additional dose early. This is recommended during local outbreaks for infants traveling to areas where measles is circulating. Infants who receive an MMR vaccine between 6-12 months still need the two-dose series because an infant’s immune system does not typically produce high enough, and long-lasting enough, antibody levels to protect them for the rest of their lives.

Does my child have to wait until 4-6 years old for the second dose?

No, the second dose may be administered as early as four weeks after the first dose. The recommendation for giving the second dose at 4-6 years old has its roots in 152 outbreaks that occurred in the U.S. from 1985-86 (see upswing on chart between 1985 and 1990). Up until this time only one dose of MMR vaccine was recommended. Surveillance of the outbreaks showed that in 101 of these outbreaks, two-thirds of the cases occurred in school-aged and adolescent patients, and only a quarter of these patients were unvaccinated. Learning that a universal single dose could still result in outbreaks, the AAP and ACIP standardized a second dose for school-aged children. Since the second dose was made a standard recommendation in 1989, immunized populations with adequate herd immunity have been void of further outbreaks. With all that context in mind, if a child under 4 years old has had one dose of MMR vaccine and lives in or is traveling to an area with measles, the second dose can be given as long as it’s been at least four weeks from the first dose.

Is the vaccine safe? What are the possible side effects?

Yes! The vaccine is safe. Most individuals receiving an MMR vaccine will have no side effects.

The temporary (usually less than 24-48 hours) possible side effects include:

- Localized reactions (such as redness, soreness, swelling and the injection site), up to 40% of recipients

- Drowsiness in 27-45% of recipients

- Decreased appetite in 21-45% of recipients

- High fever 5-12 days after the vaccine is given, up to 35% of recipients

- Mild measles-like rash, less than 5% of recipients. Also typically 1-2 weeks later

- Temporary decrease in platelets (thrombocytopenia), 1-3 cases per 100,000 recipients

- Febrile seizure in 0.04% of children under age 4 receiving the combined MMR and Chicken Pox vaccine (PAR has not, and does not, administer this combination vaccine). While simple febrile seizures are extremely scary to experience, thankfully they do not cause short- or long-term complications for the brain, slow development, or decrease learning or IQ.

Why do people think the MMR vaccine causes autism, and how do we know that it doesn’t?

In 1998, a British medical journal called The Lancet published an article by Andrew Wakefield claiming that the MMR vaccine increased the risk for autism and colitis (inflamed large intestine). This was a case series in which 12 children were reviewed, and 8 children were diagnosed with autism after the vaccine. Wakefield’s methodologies were later investigated more closely, and the article was eventually retracted in 2010 by The Lancet after investigators found that there were ethical violations (financial gain/conflict of interest) and deliberate fraud with selection/falsification of data. They also found that the children in the study were carefully selected, and Wakefield’s research was funded by lawyers hired by parents involved in lawsuits against vaccine manufacturers.

Since Wakefield’s case series and article, there have been 18 large studies in seven different countries in Europe, North America, and Asia. These studies involved hundreds of thousands of children who were grouped into 2 groups: those who received the MMR vaccine and those who did not. The two groups were matched for multiple variables (healthcare-seeking behavior/accessibility, socioeconomic background, and medical background). All 18 studies have shown that there was no difference or increased risk of autism associated with receiving the MMR vaccine.

Sources:

2024. “Measles”, Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics, David W. Kimberlin, MD, FAAP, Ritu Banerjee, MD, PhD, FAAP, Elizabeth D. Barnett, MD, FAAP, Ruth Lynfield, MD, FAAP, Mark H. Sawyer, MD, FAAP

https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/policies/position-papers/measles/

World Health Organization. Measles. https://www.who.int/health-topics/measles/

https://www.cdc.gov/measles/data-research/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/measles/about/history.html

https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/clinical-overview/index.html

https://www.cdc.gov/measles/hcp/vaccine-considerations/index.html

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/measles-epidemiology-and-transmission

https://www.uptodate.com/contents/measles-clinical-manifestations-diagnosis-treatment-and-prevention

Mina MJ, Kula T, Leng Y, Li M, de Vries RD, Knip M, Siljander H, Rewers M, Choy DF, Wilson MS, Larman HB, Nelson AN, Griffin DE, de Swart RL, Elledge SJ. Measles virus infection diminishes preexisting antibodies that offer protection from other pathogens. Science. 2019 Nov 1;366(6465):599-606. doi: 10.1126/science.aay6485. PMID: 31672891; PMCID: PMC8590458.

https://www.chop.edu/vaccine-education-center/vaccine-details/measles-mumps-and-rubella-vaccines

Herrera OR, Thornton TA, Helms RA, Foster SL. MMR Vaccine: When Is the Right Time for the Second Dose? J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2015 Mar-Apr;20(2):144-8. doi: 10.5863/1551-6776-20.2.144. PMID: 25964732; PMCID: PMC4418682.

Markowitz LE, Preblud SR, Orenstein WA et al. Patterns of transmission in measles outbreaks in the United States, 1985–1986. N Engl J Med. 1989;320(2):75–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198901123200202

Nkowane BM, Bart SW, Orenstein WA et al. Measles outbreak in a vaccinated school population: epidemiology, chains of transmission and the role of vaccine failures. Am J Public Health. 1987;77(4):434–438. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.4.434.

CDC. Measles prevention. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1989;38(Suppl 9):1–18.

Eggertson L. Lancet retracts 12-year-old article linking autism to MMR vaccines. CMAJ. 2010 Mar 9;182(4):E199-200. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.109-3179. Epub 2010 Feb 8. PMID: 20142376; PMCID: PMC2831678.