What is tetanus?

Tetanus is a nervous system disorder that results in intense, painful muscle spasms. Clostridium tetani (C.tetani), the responsible bacteria, releases toxins that irreversibly bind to, injure and block the nerves that tell our muscles when/how to relax. Many people still use the term “lockjaw” interchangeably with tetanus because a cheek muscle called the masseter is commonly affected and is the first symptom noticed by more than 75% of patients. However, muscles of the throat, neck, back, abdomen and extremities are also commonly affected causing intermittent stiff neck, neck/back arching, difficulty swallowing, rigid abdomen, tightness of arm and leg muscles, and even apnea (i.e. temporary cessation of breathing). The toxins can also cause sweating, elevated heart rate, abnormal heart rhythms, unsafe blood pressures, and/or suffocation. Symptoms develop an average of 8 days after exposure, typically progress for the first 1-2 weeks, and last 4-6 weeks; further recovery lasts months. Deep penetrating wounds are most associated with the most severe illness.

How do children get tetanus?

C.tetani is a ubiquitous bacterium in the soil. It also lives on materials such as rusted metal and glass. It can enter the body from the soil through pre-existing cuts, scrapes or other openings in the skin. More commonly tetanus is contracted by a penetrating injury such as stepping on a rusty nail or piece of glass, or puncture when baiting or using a rusty fish hook. The unique combination of being accident-prone, curious, exploratory, and relatively fearless, short-term thinkers makes children and adolescents particularly susceptible to sustaining the type of injury necessary to cause tetanus.

Can tetanus be treated?

Though washing wounds with soap and water can help prevent other bacteria from getting under the skin and causing infection, basic cleaning does little to prevent tetanus once C.tetani is under the skin. A more invasive surgical wound cleaning, called debridement, gets rid of C.tetani spores and removes dying or dead tissue that could serve as a breeding ground for the bacteria to continue multiplying and releasing toxin.

Nothing can be done to get rid of the toxin that has already irreversibly bound to the nervous system. Treatment does, however, consist of muscular injection of anti-toxin to neutralize any remaining unbound toxin and minimize further worsening.

Antibiotics against C.tetani provide limited benefit, unfortunately, but may still be administered.

Because of the risk of breathing difficulty or effects on the heart, monitoring in an ICU (intensive care unit) is typical. Powerful muscle relaxants and sedatives are often necessary “supportive” or “comfort” measures. Patients with severe tetanus may require a breathing tube/machine for the weeks it takes for the toxin to “run its course.”

How common has tetanus been in the United States and around the world?

In less-resourced countries, neonatal tetanus was responsible for an estimated 787,000 newborn deaths worldwide in 1988. Due to vaccination efforts over the next 30 years, that number was reduced by 97% to approximately 25,000 newborn deaths in 2018. True incidence of tetanus in older individuals is difficult to assess since it is not a reportable disease in many countries.

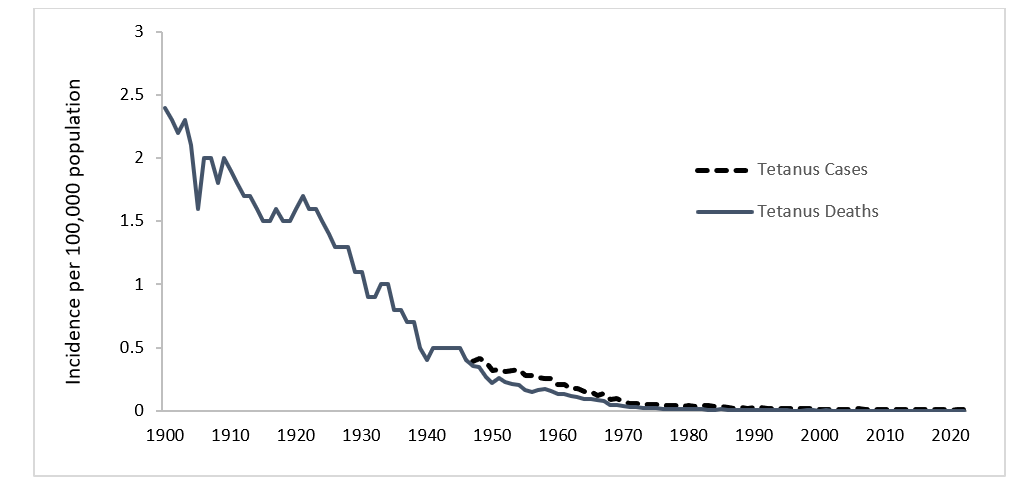

In the United States we are fortunate to have such ready access to tetanus vaccines. Consequently, only 2 cases of neonatal tetanus were reported between 2009 and 2017. In 1988, only 53 total cases of tetanus were reported in the United States. Cases have been 41 or less each year since 1998, and in 2018 and 2019 there were no reported cases in the U.S. Between 2009 and 2017, 7% of U.S. patients with tetanus died due to the illness, though all were 55 years or older. Documented cases and deaths due to tetanus have each decreased 99% since national reporting began in 1947.

How long has the tetanus vaccine been around?

The first tetanus vaccine was created in 1938.

What type of vaccine is the tetanus vaccine?

Because the effects of C.tetani on the body come from the toxin produced, tetanus vaccines teach the body how to neutralize the toxin, not the bacteria. Scientists are able to isolate and inactivate the toxin, resulting in a “toxoid” vaccine that our immune systems can recognize, make antibodies against, and neutralize. Toxoids, unlike the toxin, cannot cause disease. Diptheria (the “d” in DTaP, Tdap and Td vaccines) is also prevented by a toxoid vaccine, and will be discussed in more detail in a future blog post.

When do children receive the tetanus vaccine?

Vaccinating pregnant mothers with a Tdap vaccine dramatically lowers the risk of neonatal tetanus. Infants receive their first tetanus vaccine at the 2 month old check-up. Additional doses are administered at 4 months, 6 months, 15 months, 4-6 years old, 11 years old, and every 10 years thereafter. For reduction of side effects and number of total shots, Pediatric Associates of Richmond administers tetanus toxoid as part of combination vaccines called Pentacel (for infants and toddlers) and Quadracel (pre-Kindergarten). Additional doses may be administered if an individual has a high-risk wound/injury and is either not fully vaccinated, or is fully vaccinated but greater than 5 years since their last tetanus vaccine.

What’s the difference between DTaP, Tdap, Td, and TT?

DTaP (Diptheria, Tetanus, acellular Pertussis) The capital letters denote greater immune system stimulation, which is needed at younger ages (less than 6 years old). Will discuss the significance of “acellular” when we cover pertussis in a future blog post.

Tdap (Tetanus, diptheria, acellular pertussis) For tweens and up. Full tetanus booster. Has less diptheria and whooping cough (pertussis) immunity boosting than DTaP because of less need for individuals at that age, but still some need for maintaining herd immunity.

Td (Tetanus, diptheria) See above, but without pertussis boosting.

TT (tetanus toxoid) Protection against tetanus only. Much less commonly administered due to typical need for simultaneous immunity boosting against other vaccine-preventable infections.

Why do we have to get so many tetanus vaccine doses?

Unlike the antibodies made in response to the MMR vaccine, tetanus toxoid antibodies do not last for the rest of our lives. Many readers can likely lament over a similar temporary antibody response that leaves their children susceptible to multiple RSV infections in a winter or Hand, Foot and Mouth syndromes in a summer. Similarly, having survived a natural tetanus infection provides little-to-no lasting immune protection. Because tetanus is not spread from person to person there is also no such thing as “herd immunity” to tetanus. Fortunately, decades of scientific research have taught us just how long our bodies keep adequate levels of tetanus toxoid antibodies. When those levels drop (age-dependent), it’s time for a booster dose.

What are possible side effects of the tetanus vaccine?

The tetanus toxoid vaccine is always combined with at least one other component, so isolating the effects of the tetanus component from the others is tricky. That said, Pentacel, which Pediatric Associates of Richmond administers at 2, 4, 6 and 15 months old, most commonly causes temporary fussiness, irritability, and crying. These side effects typically last minutes, but in rare cases could last up to 3 hours. With each subsequent dose, the likelihood of these side effects decreases more and more. Inversely, fever can happen in 6% of those receiving their first dose and increase in each of the subsequent 2 doses to a max of 16% of patients receiving their third dose. Injection site tenderness is experienced by about 50% while swelling or redness occur in only 7%.

Quadracel, administered at ages 4-6 years old, causes injection site pain in 75%, redness in 60%, swelling in 40%, muscle aches in 50%, fatigue in 35%, headache in 15% and fever in 6%.

Thanks for reading the second installment of our blog series on illnesses prevented by vaccines. Next month we will cover measles and the MMR vaccine.

Sources:

2024. “Tetanus (Lockjaw)”, Red Book: 2024–2027 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases, Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics, David W. Kimberlin, MD, FAAP, Ritu Banerjee, MD, PhD, FAAP, Elizabeth D. Barnett, MD, FAAP, Ruth Lynfield, MD, FAAP, Mark H. Sawyer, MD, FAAP https://doi.org/10.1542/9781610027373-S3_019_003

https://www.fda.gov/media/74385/download

https://www.fda.gov/media/91640/download

https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tetanus

https://www.statista.com/statistics/1122819/tetanus-cases-us-by-year