What is Pertussis or Whooping Cough?

Pertussis is a highly contagious, vaccine-preventable illness caused by the bacterium Bordetella pertussis. It is commonly known as whooping cough because of the distinctive high-pitched gasping sound, a “whoop”, patients make when forced to breathe in after a bout of violent and rapid coughing. Pertussis is also known as the “100-day cough” because its cough can last for an extended period of time. Cases of pertussis occur year-round, but there is a summer-autumn peak. Pertussis circulation typically has a cyclical peak every 3 to 5 years.

How does someone get pertussis?

Bordetella pertussis is typically found in the mouth, nose, and throat of an infected person. It is spread through air droplets from a coughing patient that directly infect other individuals or contaminate surfaces, which then act as fomites (materials/surfaces capable of carrying infectious organisms). The incubation period of pertussis (the time from exposure to the onset of signs and symptoms) is typically 7–21 days, but can be as long as 4 weeks.

What are the symptoms of pertussis?

Pertussis can cause nonspecific symptoms in older children, adolescents, and adults, including runny nose and cough without the characteristic whoop, making its diagnosis and treatment more challenging. Pertussis typically has three stages in unimmunized young children and infants.

- The catarrhal phase (1-2 weeks): This phase causes nonspecific symptoms such as nasal congestion, runny nose, tearing of the eyes with redness, malaise, sore throat, and mild cough. Fever is uncommon, and when it occurs, may suggest a coexisting infection. Pertussis is often not suspected during this early phase, as symptoms mimic those of other viral illnesses. Respiratory secretions are most infectious during this period.

- The paroxysmal phase (1-6 weeks): This phase is marked by “paroxysms” or attacks that consist of repetitive 5 to 10 forceful coughs while breathing out, followed by the whoop. The forcefulness of the cough may lead to vomiting. As the illness progresses, episodes of paroxysms may increase in frequency and severity.

- The convalescent phase (1-12 weeks): During this phase, frequency and severity of coughing episodes are decreasing. During the recovery period, new and superimposed viral respiratory infections can trigger recurrences of paroxysms.

Who is most high-risk?

Pertussis is usually milder in adolescents and adults than it is in young children. Infants who are 6 months or younger, especially those who are premature or unimmunized, are at the greatest risk for hospitalization and even death. The severity of disease varies by age, immunization status, and whether the mother received the Tdap vaccine during pregnancy.

About 1 in 4 infants 6 months or younger who get whooping cough will have a complication. Pneumonia is the most common complication of pertussis in young infants. About 10% of children hospitalized with pertussis have pneumonia. Apnea, or pauses in breathing, occurred in 26% of infants < 6 months old during a 2010 outbreak that involved nearly 1,000 babies. Seizures may occur in association with apnea due to low brain oxygen levels at a rate of 1-2% of infected infants and young children. Pulmonary hypertension (elevated blood pressure that affects the lung’s blood vessels and the right side of the heart), significantly elevated white blood cell (infection fighting cells) counts, and even death have also been seen in young infants. Approximately 1% of infants less than 6 months old who get pertussis die due to one or more of the complications noted above.

What are the complications of pertussis in other ages?

In adolescents and adults, complications can include fainting, weight loss, pneumothorax (collapsed lung), sleep disturbances, incontinence, rib fractures, hearing loss, herniated spinal disc, and pneumonia. While hospitalization is less common, it may still be required. Pneumonia and seizures can also occur. In adults, sweating episodes can happen between paroxysms of coughing.

How is it diagnosed?

Diagnosis of pertussis can be based on clinical signs and symptoms, along with assessment of exposure history. Nasopharyngeal swabs (like the original COVID-19 swabs that go all the way to the back of the nose) can be obtained for culture or PCR testing. Blood tests for Bordetella pertussis antibodies can also be used, particularly in later stages.

How is pertussis treated?

Antibiotics are necessary to treat pertussis in confirmed cases. Preventive treatment for close contacts, regardless of age and vaccination status, is recommended. Early treatment helps reduce the severity and duration of symptoms, eliminates Bordetella pertussis from the nose/throat, shortens the period of infec, and reduces the spread of illness.

Supportive care measures, such as optimizing hydration and nutrition, can also be helpful. Hospitalized patients may require supplemental oxygen. In infants, gentle suctioning and well-humidified oxygen may be necessary.

How common is pertussis in the United States and in Virginia?

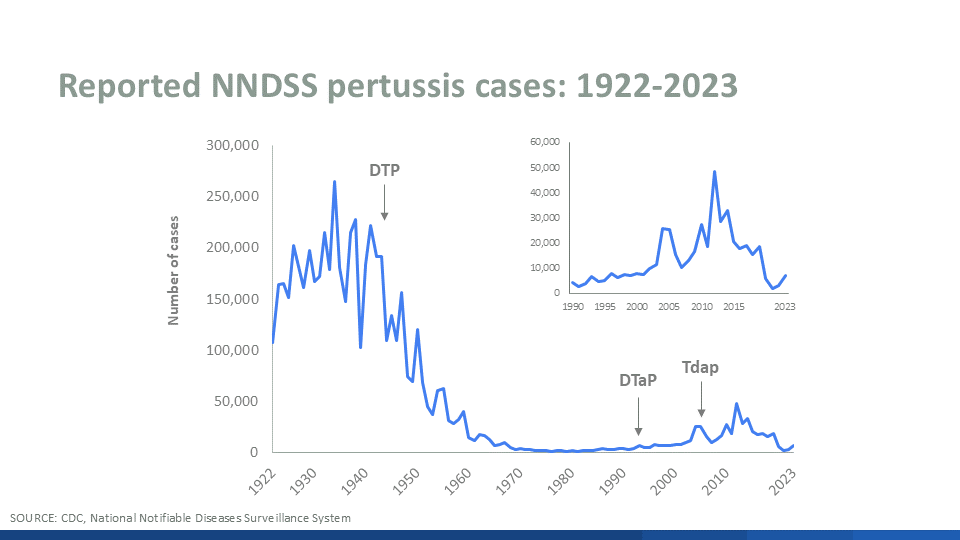

In the 1940s, before widespread vaccination, about 200,000 cases were reported annually in the US. In the 1980s, the number dropped to around 1,000 – 2,000 cases annually. Since then, cases have gradually been increasing, except for during the COVID-19 pandemic, when a decline in pertussis cases was observed. This was likely due to social distancing and masking, which helped reduce the spread of other respiratory infections as well. However, in 2023, approximately 7,000 cases were reported. Provisional data suggest that 35,000 cases occurred in 2024.

In Virginia, similar trends have been seen more recently. In 2021, there were 50 cases of pertussis reported. By comparison, in 2023 about 120 cases were reported. This number rose further to 788 in the provisional surveillance results for 2024.

The reasons for the resurgence in recent decades are not entirely clear but may include waning immunity from immunizations and improvements in diagnostic testing and case reporting. Since the Covid-19 pandemic, there has also been a decline in immunization rates impacting spread of the disease.

What kind of vaccines are the pertussis vaccines?

The first pertussis vaccines, developed in the 1920s, were whole-cell vaccines (Diphtheria, Tetanus, and whole-cell Pertussis- DTwP or DTP), which contained inactivated Bordetella pertussis bacteria. Between 1943 and 1976, immunization led to a 150-fold decrease in pertussis rates. Whole cell vaccine use decreased over time because of associated systemic and local side effects. In 1997, acellular pertussis vaccines that contain only specific components or proteins of the bacteria replaced DTwP vaccines. These newer versions, which we still use today, have fewer side effects than the original, but the immune system response is not as robust, necessitating more booster doses. In 2005, a second type of acellular vaccine, Tdap, was licensed for use. It contains smaller amounts of diphtheria and pertussis antigens and is used to boost immunity.

Currently, two types of acellular vaccines are used in the United States and much of the world. DTaP (Diphtheria, Tetanus, Acellular Pertussis) is licensed and recommended for people under 7 years of age. The second vaccine, Tdap (Tetanus, Diphtheria, Acellular Pertussis), is used for those aged 7 years and up. Neither vaccine contains thimerosal as a preservative. DTaP vaccines are often given in combination with other vaccines.

What are the immunization schedules for pertussis?

In the U.S., the DTaP primary series is typically given at ages 2, 4, and 6 months, with a booster between 12 to 15 months. The fourth dose can be administered as early as 12 months, provided at least 6 months have passed since the third dose. A booster is then given between ages 4 to 6 years, prior to starting kindergarten. At PAR, we use the Pentacel® vaccine (DTaP, Hib, polio) for the primary and first booster doses, and Quadracel® (DTaP, polio) for the second booster.

What is the dosing schedule for the pertussis vaccine and why is repeated vaccination necessary?

Immunity to pertussis, whether from infection or immunization, is not lifelong. Some estimates suggest that natural infection provides protection for 3.5 to 30 years. The current acellular vaccines typically offer 2 to 4 years of protection against pertussis, while the diphtheria and tetanus components protect for up to 10 years. After completing the DTaP series by age 6 and getting the Tdap booster around age 11, further boosters are recommended every 10 years.

It is recommended that pregnant women receive the Tdap vaccine with each pregnancy due to waning immunity. Maternal vaccination during pregnancy, preferably between 27 and 36 weeks, is associated with significantly higher levels of pertussis antibodies at birth and at 2 months, for both mothers and infants. Receiving Tdap during each pregnancy significantly reduces infection and death due to pertussis in young infants. If the vaccine is not given during pregnancy, it is recommended for mothers immediately after birth.

Keeping immunizations up to date for those around infants also provides indirect protection (i.e. herd immunity) to this high-risk population by decreasing the likelihood of pertussis exposure.

What are possible side effects of the vaccines?

DTaP and Tdap vaccines can cause localized redness, swelling, and tenderness at the injection site. These symptoms typically resolve within 48 hours without complications. Less common reactions of DTaP include poor appetite, prolonged crying, and fever. Rarely, limb swelling has been observed, but this also resolves spontaneously without lasting effects. Severe allergic reactions and shock-like states occur even much less frequently than who received the whole-cell vaccine.

For more information on pertussis in children and adults, watch this video from Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

References:

American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Infectious Diseases. (2024). Pertussis (Whooping Cough). In D. W. Kimberlin, R. Banerjee, E. D. Barnett, R. Lynfield, & M. H. Sawyer (Eds.), Red Book: 2024–2027 report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pertussis (Whooping Cough) surveillance and reporting. https://www.cdc.gov/pertussis/php/surveillance/index.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccines: Information for healthcare professionals. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/dtap-tdap-td/hcp/about-vaccine.html

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Vaccine Education Center. Diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis vaccines. https://www.chop.edu/vaccine-education-center/vaccine-details/diphtheria-tetanus-and-pertussis-vaccines

Esposito, S., Stefanelli, P., Fry, N. K., Fedele, G., He, Q., Paterson, P., Tan, T., Knuf, M., Rodrigo, C., Weil Olivier, C., Flanagan, K. L., Hung, I., Lutsar, I., Edwards, K., O’Ryan, M., & Principi, N. (2019). Pertussis prevention: Reasons for resurgence, and differences in the current acellular pertussis vaccines. Frontiers in Immunology, 10, 1344. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2019.01344

Gilligan, P. (2022, October 21). Evaluating efficacy of pertussis vaccines in children. American Society for Microbiology. https://asm.org/articles/2022/october/evaluating-efficacy-of-pertussis-vaccines-in-child

Immunization Action Coalition. Pertussis: Questions and answers. https://www.immunize.org/wp-content/uploads/catg.d/p4212.pdf

Kilgore, P. E., Salim, A. M., Zervos, M. J., & Schmitt, H.-J. (2016). Pertussis: Microbiology, disease, treatment, and prevention. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 29(3), 449–486. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.0008315

Nguyen, V. T. N., & Simon, L. (2018). Pertussis: The whooping cough. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice, 45(3), 423–431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pop.2018.05.003

Nieves, D. J., & Heininger, U. (2016). Bordetella pertussis. Microbiology Spectrum, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.1128/microbiolspec.EI10-0008-2015

Virginia Department of Health. Pertussis (Whooping Cough) fact sheet. https://www.vdh.virginia.gov/epidemiology/epidemiology/epidemiology-fact-sheets/pertussis-whooping-cough/